A Rubén Ortiz-Torres Story

Season 13 Episode 6 | 56m 17sVideo has Closed Captions

Rubén Ortiz-Torres explores his past and present in an uncertain socio-economic future.

Since the early-80s, artist Rubén Ortiz-Torres has been working as a photographer, painter, sculptor, writer, filmmaker and video producer. Often associated with the development of a Mexican form of postmodernism, Ortiz-Torres's life is a collage that explores the social and aesthetic transformations related to cross-cultural exchange and globalization.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Artbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

A Rubén Ortiz-Torres Story

Season 13 Episode 6 | 56m 17sVideo has Closed Captions

Since the early-80s, artist Rubén Ortiz-Torres has been working as a photographer, painter, sculptor, writer, filmmaker and video producer. Often associated with the development of a Mexican form of postmodernism, Ortiz-Torres's life is a collage that explores the social and aesthetic transformations related to cross-cultural exchange and globalization.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Artbound

Artbound is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMan: At the beginning of, um, of 2020, I had an exhibition at the University Museum of Contemporary Art in Mexico City, and it was an introspective exhibition called "Customatism," and that exhibition had been prepared for years.

I mean, had 30 years of work, if not more, probably, like, 40 years of work, and it was supposed to come to the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego, but then, all of a sudden, we had this pandemic.

Woman on TV: China has identified the cause of a mysterious new virus.

Man on TV: We now have a name for the disease-- COVID-19.

Man 2 on TV: You must stay at home.

President Trump: We're asking everyone to work at home if possible, postpone unnecessary travel.

[Theme music playing] Announcer: This program was made possible in part by the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture, the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, The Frieda Berlinski Foundation, and The National Endowment for the Arts, on the web at arts.gov.

Rubén: I'm starting to think that time is more complicated than what we thought.

I also think that there's a cycle, and certain things that were living seem to be repeating themselves.

So I remember when COVID hit, and then, all of a sudden, classes were canceled.

We didn't know what was happening, and yet, all of a sudden, the supermarkets were crazy.

You couldn't get rice and you couldn't get toilet paper.

I mean, I was--I was sort of lost inside the house with the family, right?

It's like we were all there, trying to figure out what to do, and I was so frustrated because I couldn't go to the studio.

I thought that I had time to do work that perhaps would be more personal.

I took advantage of being in my house to start learning how to do things in the computer, working with programs in the iPad.

It's a very immediate way to express yourself, where you don't need much.

First, I started doing collages and drawings, and then that led to the idea of what to do with those.

Once I have a certain amount of images, I started thinking in the idea of making a book.

Man on TV: ...have today declared that the coronavirus presents a public health emergency in the United States.

Woman on TV: The first U.S. case has been detected.

Woman 2 on TV: Countries around the world have now reported more than 1 million coronavirus cases.

Man 2 on TV: 2020 will be the toughest year of ours.

[Ambulance siren wailing] Rubén: When it was clear that this was a pandemic, and we had to be in quarantine, I started thinking about Albert Camus, who--"La Peste," right?

"The Plague."

[Strings playing rapidly] [Music ends] Rubén: The title of the book has a problem that a lot of my work has that problem.

I mean, it--it doesn't really translate to English, so that's why I just kept it in Spanish.

It's called "Here Comes the Plague," but "Here Comes the Plague" in Spanish is the title of a song.

[Man singing in Spanish] Rubén: Which is also one of those songs that is lost in translation, and it's a very silly song, but we all know it.

Rubén: All of a sudden, the meaning of the song was having meaning--heh heh!--which it never did to me, honestly.

Rubén: It was one of those situations where we have this problem, and--and there's no way to avoid it and--and we don't really have control of it.

And I thought, you know, obviously seems to me like we are in this kind of existential conundrum once again.

So it's not that I wanted to write exactly the same "La Plaga," but I wanted to write "The Plague," my version of "The Plague."

But eventually, sooner or later, I keep on finding more about his book and realizing that there's obvious similarities, especially when you start trying to see these other layers of meaning and subtext, and so I think that there was a kind of--this-- these coincidences, all these similarities.

At the beginning of the book, there is a piece that is called "Polycystic Landscape."

When the pandemic happened, it was of particular concern for people whose immune system was compromised, and it turns out that I have this disease called polycystic kidney disease.

And so, based on that scan with a robot, I milled cysts into foam, and we created this 3-dimensional piece that somehow, it could also be perceived as a--as a self-portrait, right, um, some kind of abstract self-portrait.

Simulacra.

I mean, simulacra is this idea, this postmodern idea that--where the representation substitutes reality, right, where the representation becomes--becomes reality.

My mother had polycystic kidney disease, which is a disease that--that I inherited.

And unfortunately, she died very young.

She was 45.

I did a couple of portraits based on old photographs of her.

I thought that there was a relation between those flowers and also the flowers that we would use in graveyards or that we use in shrines when somebody dies.

In art, for example, what is the meaning of ornamentation?

What is the meaning of decoration?

What is the meaning of--and there's a--there's a history.

I mean, modernism always wanted to escape ornamentation and decoration, and they create--and always making this critique that ornamentation and decoration were feminine or primitive or a fault, using those adjectives in a pejorative way.

And somehow, I was thinking that both the flowers and these modernist forms could be perceived as a correlative, but also have these kind of symbolic or perhaps a spiritual, other meaning that, in this case, had these very personal relation to me.

I mean, my mother was a psychoanalyst, and she was actually somebody that, uh, knew really how to listen, and, uh, she was entirely very supportive of the work, but, uh, it's sort of "How do you make work?"

It's sort of complicated, because you are responding to--to your personal life, but you're also responding to the things that-- that you see.

And so, at that time, there was a lot of talk about simulacra and appropriation, and I was looking at all these representations of flowers, for example, like, you know, plastic flowers or reproductions of them.

And yet, when I was making this work, the work, I think, was more personal because it was responding to something that I was living through, but I also think it's part of art in general, you know, it's a-- there's this constant transformation of things, and, uh, when something stops, you-- you start something else, I suppose.

I realized that I started making art, also, at a time when there was a pandemic, right?

At the time, it was the AIDS crisis, and it was not a disease that people would talk much about.

Man: Federal health officials consider it an epidemic yet you rarely hear a thing about it.

The administration's AIDS budget had little room for basic research I believe that the federal government is now doing far too little to look for effective treatments I think it made all of us wonder, "What are they hiding?"

Rubén: But it was a disease that was hitting, um... well, the--definitely the arts sector in a very strong way.

I mean, a--a lot of curators and artists that I knew died, so it was something that affected all, I mean, I guess my--my generation and, uh, and myself.

[Whistles blowing] I have a series of drawings, too, a photograph, and a painting, I believe, an old--an old portrait of a friend of mine whose name was Rubén Bautista.

And Rubén Bautista, he was a curator, um, well, originally an artist from San Miguel Allende.

It was also very important for me, too, because with him, I had the opportunity to come to the United States and Los Angeles, and with him, I was able to meet a lot of Chicano artists of the time from Texas, as well as in California.

Traveling with Rubén opened my eyes to see not just the art that was being produced in the southwest of the United States and California, but also to the economical, social, and political relations between Mexico and the United States.

But unfortunately, he--he got AIDS, and he died, uh, very young.

[Distant, faint scream] Rubén: Both pandemics have some similarities and some differences, but, um, with AIDS, people would lose weight and bodies would--would change, and it was very dramatic, it was visually scary, actually.

[Distant woman screaming] Rubén: When a hundred thousand people died of COVID, the "New York Times" published this.

When a hundred thousand people died of AIDS, in the page 17 of the "New York Times," they published this.

So that's, uh... that's a regret that I have, and I have a sense of guilt of seeing these guys that were-- that didn't even have the confidence to talk.

[Vehicle beeping in reverse gear] With COVID, it was different because we couldn't see visually the--I mean, the damage was done in the lungs, and so the thing that we had were the masks and-- and so I was wearing the mask, and I thought the mask was an interesting thing, like, had an interesting shape and--and I started making drawings of masks.

I was discovering that my face had changed because it had a mask.

Well, I've always been interested in masks because masks tend to exaggerate certain features or--or cover certain others, right?

I also think that if you have a mask, it's interesting.

It's almost like a representation on top of a representation.

It's always intrigued me, like, how--how do we recognize a face, how we start changing that face, how we transform the form.

Then, on top of that, I realized that my daughter was doing this, aiming her own way, like, she was applying makeup to herself, but all of a sudden, one day, she did this makeup that I thought it was really incredible because it was portrait of a crying woman, but the makeup really looked like a comic representation.

It was very pop.

She allowed me to photograph, which doesn't always happen, and we played a lot with the color because she has these LED lights and she changes the colors, and also had, like, a collage that she had made in the background.

But for me, it was also the situation that--that she had a lot of time, I had a lot of time, we were there, we were kind of trapped, but we were able to play...and probably the way that I communicate better with her, you know, at the end, which is the one that I know how to do, which, in this case, is taking photographs or making art and playing, doing something.

[Traffic noise] [Birds chirping] Rubén: In the case of the--of the coronavirus, we were reading about it, we were consuming media about it, but there were not a lot of images about it, and so, I was looking at images of diseases that--where the faces started becoming transformed and mutated.

So I started making these drawings and these portraits that were altered, and also that had to do with disease somehow.

I mean, they were interesting to me because, again, it's another layer of information, and you read them, we respond to them in--in certain ways, right?

And the faces became interesting to me.

I found them very painterly.

But also, these fragmentations of their faces or their bodies and the materiality of the body formally create interesting forms that become more abstract.

So, from a certain aesthetic point of view, I guess they have a particular beauty, I would say.

But that--but I'm not surprised that, you know, again, there are certain people that, well, certain people--perhaps including myself--that we look at, let's say, gore films just to see--because the special effects--[chuckling]--have this fast--create this interesting, uh, play with forms, right?

And--and they create--have their own sense of aesthetics and--so I think it was a way for me to be in dialogue with these artists, that we're playing or working in a space between abstraction and figuration.

Man: Gordon, welcome back, everybody.

We're now recording, and here's to, uh, the kickoff premiere, meeting of whatever we're gonna call this, "Friday Night...Fights" or something.

Gordon: Oscar, you want to keep time today?

Oscar: Sure.

Rubén: Right, so--so, um, I need you to--to--the host needs to say the whole-- Oscar: OK, so this is--this is also, uh, sound is recording here, so I think, uh, yeah.

Rubén, voice-over: I mean, now, when I think about Zoom, I think about social distance, I--I think about the impossibility of being together with someone, uh, as something that was related to the pandemic.

So it's--it's not a sign of something good, right?

The fact that you cannot see people, it's a reflection of, um, a problem.

Well, I've always sketched, and I've always, uh, I've always been drawing and I sketch, and there's been situations, like, for example, in school, we would have faculty meetings, and I would be there and I would sketch, you know, make portraits of people and trying to pay attention and...I was drawing the way I used to draw.

But here was--here was different because--because, all of a sudden, I had, like, this closeup, like, you know, I had this big face--heh heh!--in front of me in the monitor.

And the face was already flat, like, in a way, you don't really think graphically-- two-dimensional, became flat.

I just realized that nobody noticed that I was drawing, so I could also, like, just draw and draw and draw, and I--and I did that.

And it was very easy to do because the images are very static.

People don't move.

They are easy to draw, a lot easier than if I'm in a faculty meeting, you know, sitting, like, you know, ten meters ahead.

I just realized that it was this world of portraits.

Zoom allowed me to think in that way.

The portraits are recognizable, right?

I suppose the images could become more fragmented or more stylized.

My book evolved organically, after I noticed that I was doing these drawings or self- portraits of myself wearing a mask and then doing drawings on Zoom, and then seeing that, you know, not just my life have been affected, but also my job production and the production of images that I was making.

Man on TV: There has been a national outpouring of well-deserved support, admiration, and gratitude for our brave medical professionals who risk their lives every day to save lives in this pandemic.

We give them a special thanks tonight.

[People cheering, applauding] Man, clapping: Yeah!

[People whistling] [Clamoring continues] Man: Rock 'n' roll!

[Cheering, clapping, and whistling continue] [Whistle blows, fades out] Rubén: There's these moments of crisis that force us to rethink about what the hell is happening with humanity, where are we going, and--and exacerbate the absurdity of all of these things, no?

[Siren blaring] Woman on TV: Overnight, nationwide unrest and more chaos in Minneapolis, where Officer Derek Chauvin is now charged with-- [Crowd chanting "Black lives matter!"]

Rubén: Police brutality was happening, and people were demonstrating and then we would come out to the streets and then we would march, and it was surprising.

I mean, these marches were very compelling.

People were reacting against something that should not happen--[scoffs]--that just should not happen, and yet I--I saw that there were connections to other situations, right?

All of a sudden, why does these things happen, right?

Why--why is there--why these kinds of abuses of power can happen?

It obviously happened for economical reasons and political reasons, and there's a history for it.

And unfortunately, it's the history of this continent and, you know, it's a history that comes with colonization and comes with, uh, with certain forms of oppression.

Man on bullhorn: Hands up!

Crowd: Don't shoot!

Man: Hands up!

Crowd: Don't shoot!

[Man shouting indistinctly] Rubén: There's a dialogue with a lot of artists in the book.

One of them is Camus, but another one is Goya.

So these are the artists that have questioned that.

'Cause Goya has this series of etchings that are called the "caprichos."

In this work, he's really questioning all these absurdities, I mean, all these, uh, irrational absurdities that are--that I guess he sees in-- it happening in Spanish society and in Europe at the time.

In one of the most famous etchings in it, it has the famous phrase of "the dream of reason produces monsters."

Trump: Whatever happens, we're totally prepared.

I mean, view this the same as the flu.

Supposing we hit the body with a tremendous, uh, whether it's ultraviolet or just very powerful light.

And I see the disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute, one minute, and is there a way we can do something like that?

And we've done some things that, as you know, have been very popular.

Rubén: I was thinking in my book and my collages and my drawings are some--like, my version of those caprichos, right?

As these sort of personal notes, where I was trying to deal with these absurdities, too.

And his--his work is so amazingly contemporary.

Heh!

I mean, it talks so much about these times.

I mean, if you want to understand what is happening now, look at his--look at his etchings, and you're gonna see the--the folly of humanity there.

Trump: We're going to build a wall.

It's going to be built.

Rubén: And we're still seeing that, this return to fanaticisms and fundamentalisms and nationalisms and--and all these forms of extremism.

I think of art not as a--as an extension of sadness or rational thinking, but, in fact, as something to counterbalance that and as something to humanize that, to--to add this other questioning of that.

So, you know, juxtaposition, recontextualization, appropriation, the idea of culture jamming, all these strategies, "what's in the meaning of an icon?"

are things that I am constantly doing.

During 2020, I was invited by this gallery in Barcelona called DECESO Gallery to participate in this project that was very simple.

It was just basically to create a black-and-white image that could be reproduced in a regular printer and then paste it on the street.

It was thinking in certain forms of photo montage, that that also--that preceded techniques that I was using.

Because before memes, before Photoshop, before text an image, there was John Heartfield, right?

I mean, John Heartfield's this guy that--that eventually started reusing propaganda to revert it against itself, right?

I mean, he was working, he was using Nazi propaganda, as a critique Nazism, right, and fascism.

And the image that I used was a photo montage where, based on these John Heartfield, uh, very well-known, uh, photo montage, where he had Hitler, where Hit-- and Hitler had an X-ray, uh, image of his thorax, and then you could see that he was following money.

And then what I did here is that I alter--I mean, I used an X-ray of--of a COVID patient, and then I created these collages.

It was of these--all these, uh, Presidents that actually have COVID because they didn't want to use masks, and--and so I created this collage and--and it was timely, but it was, again, I mean, it came from the the Second World War, but it was still reading very clearly, like, you know, like, it totally made sense.

[Woman shouting in Spanish] [Protestors respondingin Spanish] Rubén: We are in a moment where, of course, like a whole--this whole idea of progress is being questioned, right?

There is something very Nietzschean about this.

Doesn't seem that we learned from the past because I see that there's these cycles, right?

I don't think we're nec--it's necessarily the same, but it seems that, uh, that there's this sequence of events that tends to repeat certain things, uh, certain behaviors, certain things that probably happened.

And unfortunately, it's the history of this continent, you know.

It's a--it's a history that comes with colonization and comes with, uh, with certain forms of oppression, and that colonization also comes with disease.

One of the first consequences of colonization was the spread of, uh, of disease, particularly smallpox that killed millions of Native Americans, right?

And actually, smallpox was probably, way more effective than--than gun and iron, right?

Heh!

I mean, you know, than these technologies, that they were not familiar with that also were used to submit them, right?

So then there's this history, right?

It's like there's this history of how these--these diseases were used as--as weapons, and so I thought it was not a coincidence--[chuckles]-- that, again, in a moment like this, with social contradictions and the differences would exacerbate with this disease and how the disease was treated and--and all that.

Crowd: No more masks!

No more masks!

Rubén: It was also a surprise to me that so many people would also not want to confront the disease or would deny science or would, like have these other magical thinking as to how this thing would have to be addressed or confronted or these sort of denials.

Woman: Nobody is sick, sweetheart.

Woman 2: OK, go for it.

Woman: Educate yourself.

These-- and I--if I ever come back here again, and this thing is proven to be a hoax, I want an apology from each and every one of you.

Rubén: And then, I guess, I realized that, you know, if you read Camus, at the end, Camus, the book is not about a disease.

It's about colonization.

[Indistinct chatter] [Scattered people whistling] Man on TV: Cleveland baseball is parting ways with its logo, Chief Wahoo.

Man 2 on TV: The controversial logo for the Cleveland Indians will be officially eliminated from game uniforms.

Man 3 on TV: ...many saying the logo is racist.

Man 4 on TV: I got the smiling face of racism smiling right back at me.

Man 5 on TV: Chief Wahoo, it's the tribe!

And that's our logo!

I like Chief Wahoo!

Rubén: There's certain logos that have been used by teams that were considered demeaning by certain ethnic groups, right?

The Cleveland Indians logo, Chief Wahoo, and these are images that I grew up with that that I've been thinking about since I was a kid...

I did this painting in the eighties before there was really a polemic about Chief Wahoo.

I juxtaposed the image of Chief Wahoo from the Cleveland Indians over an Olmec head, right?

And I was quite young when I did that, but I was conscious that these two representations were stylistically very different, that one was a cartoon and was a very simple and direct thing, and the images that I was exposed to as indigenous representations or indigenous art were very complex, actually, were very elaborate and very complex, were, like, the opposite.

The cartoon was flat, it just had two colors.

I don't know if I was fully aware of the--of the way this cartoon was perceived in the United States in terms of the--its--its stereotypical reduction of--of how a Native American gets represented, but I was definitely aware that it was something more simplistic and--and, uh, and shallow than the richness, in this case, of an Olmec head, but could be any, uh, Native American representation.

And, interestingly enough, in Mexico, the Little Leagues all have names of--of ancient Mexican civilizations.

So I used to play in the Mayan League, and I used to play against the Olmec League, and we never saw that as--as, uh, stereotyped, uh, because, in fact, the way--the way these--I mean, the names of these teams in, like, in the context of Mexico were perceived to be part of the history of Mexico, right?

I added--I added a text that, uh, underneath, you can see this text that says, "Viva el Mole de Guajolote," like, means, like, "long life to Turkey mole," and that text actually comes from a--from a Manifesto of the Estridentistas, right?

The Estridentistas were this avant-garde movement from Xalapa, Mexico.

I mean, who would have thought?

But in the beginning of the 20th century, these Estridentistas were doing its Mexican version of--of a modernist avant-garde, right?

So they were reacting to dadaism and--and, uh, and futurism and-- and, you know, these avant-gardes, uh, and--and so I guess it was a sort of response to Thanksgiving, and the image of Chief Wahoo, uh, in this more recent version of the painting.

It's been--it's been pixelated since the--since the logo has been, uh, has been prohibited.

So I--I like this grid that, uh--I mean, this--you create a composition with--a color composition like this grid color composition that looks like a modernist painting and then becomes something else.

What is the meaning of a symbol?

I mean, the meaning of a symbol is it fluctuates.

Problem with symbols is that symbols are--are conventions.

We have to determine the value of a symbol and agree on it.

A group of people has to agree, right?

It's like, how do we know that in a traffic light, that red means stop and green means go?

We have this flag that was one of the first flags that was used in the American Revolution, uh, in opposition to the English flag, you know, to represent the--the independence of the-- of the colonies.

And that flag has been used by the right lately.

And it--it's strange to me because it's also often--the word "libertarian," for example.

The word "libertarian" used to mean anarchism, and a lot of ideas that have to do with freedom and anarchism, I mean, have been appropriated and used in different contexts.

Man: Jesus Christ, we invoke your name!

Amen!

Crowd: Amen!

Man: Let's all say a prayer in our sacred space.

Thank you, Heavenly Father, for this blessed--this opportunity.

Thank you, Heavenly Father, for--for being the inspiration needed to these police officers to allow us into the building to allow us to send a message to all the tyrants, the Communists, and the globalists that this is our nation, not theirs.

Man: Yes!

Jake Angeli: That we will not allow America, the American ways in the United States of America to go down.

Thank you, divine and omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent Creator, God.

Thank you for allowing the United States of America to be reborn.

Thank you for allowing us to get rid of the Communists, the globalists, and the traitors within our government.

We love you and we thank you.

In Christ's holy name, we pray!

Men: Amen!

Rubén: The original flag, this snake, is supposed to represent America.

It's a rattlesnake, so it's indigenous, from America, but then, now, in some of these, uh, anti-immigrant rallies, they seem to assume the rattlesnake, that it's supposed to bite you if you help the snake, and it's supposed to be this metaphor of--of how foreigners, uh, are intruders that might bite you.

[Crowd shouting indistinctly] Rubén: "No me chinguen," it's actually--the meaning is very close to "Don't tread on me."

It's just that it's, uh, it's slang, it's a more vulgar way to say, "Don't tread on me."

You know, in juxtaposition, there is, like, you have the original, the snake that comes from the "Don't tread on me" flag that is--I guess it's called the Gadsden flag.

And the snake--obviously, there's also a snake in the Mexican flag, but it's a snake that it's being eaten by, uh, by an eagle.

And supposedly, according to the myth, the Aztecs leave Aztlan, looking for this place where the gods tell them to go, which is where a snake is being eaten by an eagle, and they found that in the--in this lake where Mexico City is, uh, and that becomes a symbol of the Mexican flag.

So, up here, we have these different two--these two juxtaposed mythologies, contrasted with each other and creating this new, strange, I suppose, national symbol of who knows what.

Man: Under the International Bridge in Del Rio in Texas, a camp that's become home to thousands, and which reveals yet another crisis at the border in America.

[Men shouting] Reporter: It is these pictures of Border Patrol agents on horseback, pushing migrants into the river, that have caused so much anger.

For some, they carry the echoes of the worst chapters of American history.

Woman: What we witnessed takes us back hundreds of years.

What we witnessed was worse than what we witnessed in slavery--cowboys with their reins, again, whipping black people, Haitians, into the water.

[People shouting indistinctly] Border Patrol agent: No!

Rubén: It's just--again, it's this image that circulates... that circulates on the news, right?

And it's an image of the--there's this Border Patrol agent on a horse, chasing a Haitian immigrant.

But it's an image that bothers me because it really triggers all this unconscious of images that come.

When I saw the image, I mean, I remember that a lot of African-American people were relating this image with images that they--that would remind them of the plantations and such.

And it's not just American culture, to be honest with you.

I mean, it even reminds me of the images of the Conquest, as the image of the Conquistador and the horse that becomes this--you know, for the Indians, in fact, it was the same animal, the horse and the--and the Conqueror, right, and the Conquistador.

And, uh, and then the, you know, yeah, yeah, and, you know, this colonial image of power.

I mean, this is the biggest issue we have to solve in the continent.

This is the beginning of the history of America, and by "America," I'm not meaning the United States.

I'm meaning Columbus shows up here, and then that's the beginning of the problem.

I mean, how are we going to be able to create that society where we would become functional?

So, in that sense, uh, whether you call it racism or colonization, those are the structures or systems, right?

Obviously, it reminds me images of--of westerns, is this image of the cowboy and the massacres of the Indians.

Yeah, I--it's painful, the image is.

Heh!

Yeah, I mean, it reminds me--I mean, of course, the title of the--of the--the title of the collage is the title of--of a movie, of a western that I made up when I was a kid, right?

That the West is a pest, which, again, coincides--I just called it "The West Is a Pest" because it rhymed, right?

"El Oueste es Una Peste," and I made my little pacifist western with, you know, with my kids in grammar school.

Uh, but again, it coincided with this--with the title of the book, right?

With the--with the idea that the pest, this--yeah, of this--this circular thing.

Man over radio: Minnesota state statute 609.50... [Scattered explosions] [People shouting indistinctly] Woman on TV: The Minneapolis area saw another night of angry protest over the killing of Daunte Wright.

The unarmed Black man, just 20 years old, shot dead by a White police officer during a traffic stop Sunday.

Woman: I'm a beginner shooter, and I can tell the difference between a weight of a gun, the trigger of a gun, versus the trigger on a--a Taser?

[Crowd shouting indistinctly] Rubén: I realized, when I was in the street, taking photographs, that--that the only other moment in my life where people were wearing masks was during the Mexico City earthquake.

[Rumbling and thudding] [Crashing] Rubén: Well, in September 19th, in 1985, when the Mexico City earthquake happened, I was asked to go and document this important historical event.

So I took my camera and took the subway.

Most of the damage was localized in the center of the city, and--and I went there.

When I was taking those photographs in Mexico City, I--I was so scared that I did a lot of double exposures.

In that way, perhaps, that relates to the kind of collages that I'm doing now or these kind of juxtapositions, where things, uh, juxtapose something, you-- you get multiple layers of information.

It was a--it was a moment of crisis, not just--not just of natural disaster, but also, the government was so outstretched it couldn't really respond to the magnitude of the problem.

Even society had to somehow organize by itself.

Interestingly enough, I was thinking that here, we also had an extreme situation where we were in masks, and also, we were dealing with serious problems with democracy.

I mean--heh!

It's a different kind of disaster, but the signifier of the mask, for me, at least, represented a disaster, a public disaster at the large scale in the city.

When we say that we're mortal, it implies an end, but I'm starting to think that end is also beginning, so the process of life continues.

I mean, I guess in the book, we see these cycles, right, and those cycles are cycles that, I guess, are-- start with life and death, right?

Reporter: This normally lush, quiet area of north San Diego County tonight is a scene of abject, shocking horror.

Rubén: At some point in the nineties, there was an incident in San Diego, where, in Rancho Santa Fe, this community of people committed suicide because they were supposed to take off on a--on a comet that was happening close to the Earth.

And I remember seeing these photographs, and they were wearing these black Nike shoes.

Then, at some point, I was in a--in a car show where I saw this--this pickup truck is splicing in different parts and becoming this abstract object that looked to me like a space rover.

And then I was invited to participate in that exhibition called INSITE.

My idea was to make a dancing pickup truck that would project images, both in the car shows as well as the gallery or in the museum, and that you could drive this art piece and go through these borders in these different contexts, right?

That I could go to Tijuana or Los Angeles or San Diego and present it in these different places.

And so we customized the truck, and we've painted it like a Border Patrol, but it was a Space Patrol.

It was a--it was called "Alien Toy."

And then I created this video that at the time, I thought that perhaps it had this--this very sci-fi, crazy narrative about it.

[Distorted voice speaks indistinctly] Man: ♪ Yo, yo, it's all good ♪ Rubén: Science fiction has always been an allegory of social issues or problems that exist in--in society, right?

Often an allegory where two civilizations encounter each other and, unfortunately, often confront themselves violently, which I think it has to do, probably, as a representation of colonization and the discovery of America, so on, so forth.

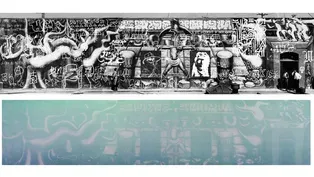

Arguably, the first important modern art piece that was produced in California was the mural "Tropical America," who was also painted by an immigrant, right, David Alfaro Siqueiros.

He was--he was commissioned to do that in Olvera Street.

He came and painted this mural that was, again, a representation of, uh, indigenous ruins, right, expressing somehow the exploitation and colonization of Native American communities in the Americas.

Needless to say that the woman that commissioned the art work didn't like it and eventually painted it white.

Man: F.K.

Ferenz, the director of the Plaza Art Center, orders that all portions of the mural visible from the street be whitewashed.

Two years later, the entire mural is covered.

Rubén: But before the painting was whitewashed, Siqueiros made sure that the "Los Angeles Times" would take photographs of it and that it will be published.

And they--and the mural eventually was censored, it was--and it was destroyed.

What I was thinking when I made that painting is that somehow, Siqueiros was making a figurative mural that had this narrative and this political message, but I think he was also making a performance, he was making an action because somehow he was aware that the painting was going to be destroyed, was going to be defaced.

It seems that the piece in its day went viral, and years afterwards, there's been these attempts to restore it or to at least recover it as much as it is possible.

Eventually, the Getty Center end up spending a lot of money trying to recover the painting and creating the space for it.

Finally, Siqueiros achieved what the mural was supposed to be-- his imagined growing of Los Angeles, and I'm thinking that if I keep adding and adding and adding, eventually it would disappear, but in--again, that goes back to this idea of the baroque, how extremes touch each other, right?

If you make something baroque enough, it becomes minimalist.

It's like a ghost of the mural.

[Crowd cheering] Man: It was put up here in broad daylight, and so he should come down in broad daylight.

TV anchor: That statue of Columbus had stood for nearly 80 years, but came down in just a matter of seconds.

TV anchor 2: Similar monuments are being removed around the country.

[Crowd cheering] Woman: It was the start of a racial reckoning so many of us never expected to see.

[Crowd chanting "Tear it down!"]

Rubén: We were living through these processes where some monuments were being removed, right?

And of course, the first monuments that were considered more offensive were the monuments of the Confederacy that have been problematic and have been the symbols of slavery and racism.

So they've been questioned, and also, their artistic value has been questioned.

But that also led to the questioning of all sorts of other monuments.

In the case of Mexico, for example, the Columbus monument.

Or in Los Angeles, the monument to Junípero Serra, right, like, the, like, you know, the missionaries or, in New Mexico, to, uh, Oñate.

Here in the United States, it had to do a lot with the--with the Confederacy and with issues of racism, whereas, in--in Mexico, a lot of the protests had to do with police brutality against women.

And I guess, also, in Latin America, not just in Mexico, because you also had all these other feminist chants that were coming from Chile and these interventions in public spaces, where often these monuments are displayed.

Woman on TV: Millions of women around the world took to the streets Sunday to mark International Women's Day.

In Mexico City, at least 60 people were wounded as riot police confronted protesters carrying signs that read, "You're killing us" and "We want to live without fear."

[Women chanting in Spanish] Rubén: And these monuments are-- are monuments not just of colonialism, but also they're patriarchal monuments, right?

They happened to be always guys, you know, these--these Conquistadors, and so there's the requesting of these monuments, and in the words of de Kooning, "destruction is a creative process" and destruction as a creative process, again, is something that sort of, uh, relates to this, uh, idea of the--of the cycles.

[Techno music playing] Rubén: There are different ways to block or destroy or deface an image, right?

In the case of a--of The Glitter Revolution or what I did with those paintings is that you cover certain symbols or certain signs, uh, with different materials, right?

It could be painting.

In this case, it was glitter.

The glitter in itself has also-- signifies something else, right?

So there's a new meaning that gets to be acquired by--by, you know, like this, uh, covering things or throwing glitter at something.

One very dramatic example that has this particular symbolism is--it's burning something, right?

So there is, uh, I guess this-- this very dramatic gesture, burning a flag.

But the flag is not really-- again, it's just a representation, right?

It's a-- it's a symbol that, in this case, represents this abstract idea about country.

What happens when you burn the flag?

I mean, you burn a flag and then you--you produce ashes, right?

And these ashes, something else comes of that.

Uh, you don't really--really destroy the--the thing.

I mean, you just transform it.

And with these ashes, I--I produce these other--other flags, right, these monochrome flags, these black flags, where pigment, where--where ashes were used as pigment to make ink.

which goes, again, to these discussions about iconoclasm and--and, uh, the negation of symbols, the negation of ornamentation, what is the meaning of ornamentation?

So, for me, the politics of these are very interesting, are very fascinating, are very--I think a lot about them and why do we like what we like, why-- why do we find beauty in certain things and not others?

This idea of, uh, of an American Black Flag, which is a flag that often we associate with the anarchist flag, which is, I guess, another representation of--of freedom, I suppose.

Whether if it's Jasper Johns or David Hammons, it seems to me that it really becomes a symbol of freedom when there's a freedom to create it in different versions and interpretations.

But also, for me, it's a way to also claim as I become a citizen to make my American flag, American flag that I would say represents me.

And one of these flags--actually, it's interesting because it has color and you can see blue, white, and red on a black flag; when the light hits in a certain way, the flag would appear.

There's one of the images where we look at this, uh, flag being burned in a barbecue.

On the background, there's an image of the fires in California.

But those fires, if controlled, are necessary to recycle the forest, right?

So perhaps we should--we should have controlled fires of flags--[chuckling]--to make sure that the flag, it grows in its proper way and doesn't turn into a monstrosity that eventually can lead to a major fire.

But the negation of representation of symbols becomes a symbol, too, as it becomes a symbol of the-- [chuckling]--negation of representation of symbols.

During the pandemic, during the protests against police brutality, there was a--I believe it was called a Black Tuesday, where everybody started just displaying a black image on Instagram, so much so that that day, the minimalists became pop art because it just appeared in everybody's feed.

As we were discussing this whole issue about Black Lives Matter, I created this collage that-- together, all these black paintings, I suppose, they form a big, black collage.

But inside of them, they are all sorts of different black paintings, produced with all sorts of different intentions, right?

We have from the Goya's black paintings to Malevich, "Black Square," uh, to this Mexican painter, Beatriz Zamora, who is--all--the only things she make in her life, like, uh, she's spent years just making black paintings.

There's a black painting by, uh, Antoni Tapies, there's a black painting-- there's a black painting by Motherwell with a very beautiful quote about--about black--black paintings, and he associates black paintings with Spanish art and--and what his meaning of black is.

And--and I always, uh, I've always been fascinated by those dark, black paintings of Goya and the chiaroscuro and, uh, and the use of black in Spanish painting, even--even "Guernica," right?

Art is a form of expression, right?

And it is a particular form of expression.

You know, mathematics expresses numbers, expresses quantities.

Art expresses emotions.

And the--I think, also, art, it's a form of philosophy.

It's not just expressing emotion in its purpose, but it's also a way of thinking, a way of understanding and expressing certain things that, perhaps, other forms cannot do.

I mean, I--[scoffs]--I guess I tend to react emotionally to most things.

That's why, perhaps, I--I like art and I do art, but, uh, but certainly, things happened that were close to me.

I mean, uh, my father died during this period and, uh, and that got me thinking, you know, all sorts of things.

My father was a very funny character.

He was a very sweet guy, and--and he was very funny and he always liked my cartoons.

I used to do cartoons when I was a kid, I used to do comics and cartoons, and he always thought that I was a cartoonist.

He always said, like, "Oh, you're always, like, you know, making cartoons," which I thought was interesting because I guess I have spent my whole life trying to be an artist and trying to make serious art and trying to make paintings.

At the end, maybe he was right.

Maybe I'm interested in how painting can make other kinds of commentaries in the use of humor and the use of politics and narrative, and these other things going on with the image.

[Warner Bros. cartoon theme music playing] Rubén: What I felt at the time, it would be finally the end, you know, the end after the end, which is when the vaccine comes.

Porky Pig, stuttering: That's all, folks!

Rubén: And even though I had 3 vaccines--[record scratches]-- eventually get COVID, and I freaked out because I'm a high-risk--heh!--patient.

So eventually, I'm sent to these monoclonal antibody treatment, and then the two nurses that are giving me the treatment, who happen to be these African nurses, I start talking with them, and then they tell me that they don't have medical insurance.

And I--"How can you not have medical insurance?"

And they can't afford it, and I'm here, the privileged guy that is getting this very fancy treatment that probably most people in the world can't get.

So at the end, the book ends up like this fotonovela with this little commentary and--and I guess the book ends--it doesn't end.

We always have known that there's the possibility of having these--these viruses, right, or having these epidemics, and it's not gonna be the last one.

So, in a way, when I look at how the disease sort of spread and worked, it's very similar to the plague that Camus described-- heh!--happening in north of Africa.

I mean, it still takes a few years and, uh, and lingers and creates all these other social and political problems.

There's different characters in the book of Camus, right, and there's this very existential question, and this thing is coming, and there's nothing you can really do about it.

And, uh, and some people don't do anything, some people try to avoid it, and they die.

And there's a character that-- that you are listening to, the point of view of a particular character that at the end reveals himself, right?

And this character is a doctor, and the doctor--the doctor is particularly interesting to me because he cannot solve the problem, he cannot, but he still fights.

And I don't know if this is a legacy, but I would like to see myself as that.

I don't think I'm gonna solve the problems, but that's not an excuse to not try.

[Man singing "La Plaga" in Spanish]

How Rubén Ortiz-Torres Reclaims Symbols of Oppression

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S13 Ep6 | 8m 52s | Ortiz-Torres uses destruction as a form of creation in his decades-long body of work. (8m 52s)

Rubén Ortiz-Torres Remixes 'América Tropical'

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S13 Ep6 | 2m 11s | Ruben Ortiz-Torres' 'White Washed America' recreates whitewashed mural "América Tropical." (2m 11s)

A Rubén Ortiz-Torres Story (Preview)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S13 Ep6 | 30s | Rubén Ortiz-Torres explores his past and present in an uncertain socio-economic future. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Artbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal