EAST episode

Season 17 Episode 1 | 54m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

EAST highlights diverse expressions behind modern craft in the eastern region of America.

EAST explores the intersection of history, culture and contemporary craft in the eastern region of the US. As a nation of immigrants, these American stories, from a fabric flower factory to a silversmith to a potter and more, highlight the diverse expressions behind modern craft. Featuring M&S Schmalberg, Bisa Butler, Colette Fu, Roberto Lugo, Ubaldo Vitali, Paul Revere House, Helena Hernmarck

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

EAST episode

Season 17 Episode 1 | 54m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

EAST explores the intersection of history, culture and contemporary craft in the eastern region of the US. As a nation of immigrants, these American stories, from a fabric flower factory to a silversmith to a potter and more, highlight the diverse expressions behind modern craft. Featuring M&S Schmalberg, Bisa Butler, Colette Fu, Roberto Lugo, Ubaldo Vitali, Paul Revere House, Helena Hernmarck

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Craft in America

Craft in America is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Education Guides

Download Craft in America education guides that educate, involve, and inform students about how craft plays a role in their lives, with connections to American history and culture, philosophies and science, social causes and social action.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ Man: We're the last remaining factory that manufactures artificial flowers.

The company was started by my great-uncles.

They were immigrants looking to provide for their family, and so they picked a craft.

Why not flowers?

Woman: I am working on a series of quilted portraits, using these glittery African fabrics.

I want Black people to see something that speaks to them about where they came from.

Second man: I consider silver the most beautiful metal, much more beautiful than gold.

As you walk around an object, you see that all the reflections change.

In my work, I try to make silver dance in light.

Second woman: I learned how to make my own pop-up books, and then I incorporated pop-up mechanisms with my photographs.

So, it just seems like magic.

♪ Third woman: When I'm weaving, I forget everything else.

It's a great pleasure.

It's what I've always wanted to do.

I've never ever thought I would do anything else.

Third man: The work I do is primarily representing the community that I come from.

My first introduction to art was graffiti.

And so I started to draw and paint.

I told myself that I was gonna have a career in the arts at all costs.

♪ ♪ [Traffic sounds] Adam: You walk New York City, the garment district in particular, and you look up at these buildings, and you have no idea what's going on inside of them.

♪ At M&S Schmalberg, we're a fourth-generation family business that manufactures artificial flowers.

♪ We are the last factory in the country doing this.

♪ Warren: Aha.

Adam: What's up?

Long time, no see.

Warren: Mwah!

You grow up, and your dad is a plumber or an electrician, a flower man.

I never really processed that he was the only flower man.

Warren: Hello, ladies.

Lucia, Miriam.

I'm retired, but I worked at M&S Schmalberg almost 50 years.

Look at you.

How are you?

Woman: Fine.

Warren: Sometimes I'll come back just to help them out, because it is a family here.

Beautiful.

Very nice.

What we do here is we take fabric of any type and create artificial flowers and leaves and petals, still making them by hand, as we have for 109 years at this point.

♪ Adam: The company was started back in 1916 by my great-great uncles, Morris and Sam Schmalberg.

They were immigrants looking to provide for their families.

And so, they picked a craft, and why not flowers?

Warren: In those days, there were probably 30-40 flower companies in Manhattan alone, and some of those shops had as many as a hundred people working for them.

[Machines whirring] What's up?

How you doing, buddy?

- I'm good.

You?

-I'm good.

What's up, gentlemen?

Mr.

Warren!

All right.

Senor.

-Mr.

Warren.

-Esta bien?

Yeah.

Very good.

Father-and-son team here.

[Machines whirring] Warren: Right after the war, my dad came to America.

He was a Holocaust survivor.

He was in his teens when he was sent to a concentration camp.

His mom and dad and his two brothers and his sister perished.

After surviving the camps, he was in the Nazi death marches.

But one morning, he was woken up by an American soldier, who said, you know, "Hey, here's some water.

You know, it's over.

You're gonna be okay."

And he said to my dad, you know, "Who's left?

Who can we contact?"

And my father said, "I don't have anybody, but in New York, in America, Schmalberg Flowers."

And this American soldier contacted Morris and Sam, and they got dad on a boat.

He stayed in their attic, and he would come to work and learn the business.

When Morris and Sam passed on, my father bought it from their spouses.

In those days, it was the thriving garment center.

These streets were lined with factories.

We were the flower guys for the dress industry.

And there were other flower guys for theater, other flower guys for hats.

And they all just couldn't make it.

Adam: The first thing we do when we get any material is we cut it into panels about 50 inches square.

And there's a few different starches that we use to give it extra body.

You wring it out as best you can.

Then you stretch it on the frames to dry.

Once the fabric is starched and dry, we make layers out of it.

We then take our vintage dies and cut out the flat petals.

[Machine whirring] You're cookie-cutting, just whatever shape the die might have.

And we have hundreds of different dies.

Most of them are flowers, but there's leaves, there's butterflies.

It started out like these, with the handheld dies.

And they're beautiful.

Like, this is a four-leaf clover, or four paw we call it.

And you see the detail on that as opposed to this one, totally different.

In the old days, there was no machine like Alex is cutting.

And everything was cut with a mallet and a boom.

[Mallet pounds] So, imagine cutting a die like this, this heavy die-- it's probably 10, 12 pounds-- cutting this through fabric by hand.

♪ Adam: The next step is the embossing.

The molds date back, some of them, to the late 1800's.

And they resemble a waffle iron.

You take your flat petal, put it between the molds.

♪ And with pressure, heat, and the starching from before, you're embossing the petals.

Now they've been cut, they've been pressed.

So, then finally they go to assembly, where we put them together to make the flowers.

♪ Warren: We're not horticulturally on the money here, because it's not nature, but we do some beautiful things close to nature.

♪ Adam: The whole business is a combination of tools that are irreplaceable and people and skills that are irreplaceable.

♪ Hey, Al, when you're done with that, I have two orders for Katherine.

Alex has been with the company since I was a kid, almost 40 years.

-No problem.

-Thanks, Al.

Miriam worked with my grandpa Harold.

She's a master flower maker, master artisan.

What if we did something with wired fours, and then you could make a center?

What do you think?

Miriam: We don't have a...a petal.

Adam: I defer to them.

I respect the experience that they have.

What if we take one of the poinsettia petals?

That make sense?

Miriam: We'd have to create the flowers.

Adam: Okay.

All right.

Miriam: When I am creating the new flowers, sometimes my mind comes a flash, and I stop, and I create something.

If they like it, I love it.

♪ Warren: Nowadays, sadly, there's no garment district.

You don't see trucks in the morning.

You don't see pushcarts on the streets.

Artificial flowers are coming from offshore, copies of our flowers.

But today, there's enough domestic things between theater and fashion and operas and TV shows that keeps us okay.

And then there's the Met Gala, where all the couture designers dress the stars of the world.

If it's a season where flowers are in, our stuff is on the red carpet for the event.

♪ Adam: One of Vera Wang's senior designers asked if we could make a parrot tulip.

So, I went on Google.

I looked up pictures of a parrot tulip.

We've been making that flower.

It's about 14 inches.

It's been worn by Emily Ratajkowski.

And then they asked if we could make even larger ones.

They sent us 50 yards of this chartreuse fabric.

It was worn by Gwen Stefani.

Big flowers, a lot of work to make these things.

♪ Each generation brings something different to the table.

Now there's social media, there's online platforms.

These have become a big part of our business.

Every day somebody comes in here, tells me they found us on Instagram, and "Can I buy a flower?"

to which the answer is always yes.

♪ Could you imagine what they would think that we were still here, that I'm sharing Instagram videos, selling flowers on Etsy... in 2025?

We're very lucky.

We're very lucky.

You've got grandpa up there keeping an eye on both of us.

Yeah.

Warren: You know, my dad was that Holocaust survivor, and I think his skills and his thinking were inherited to me and to Adam.

He set a path for us, you know, to keep it going.

You know, we love this.

We love making flowers.

♪ [Train rumbling] ♪ Bisa: All of us understand fabric.

From the moment you're born, they wrap you in a blanket, they put that little hat on your head.

Your whole lives, you're surrounded by fabric.

And I think it becomes a deeper understanding of what is being communicated in my portraits, because nobody has to sit you down and explain to you the rules of this.

This is fabric.

It's touching you at all times.

♪ Dalila: Bisa Butler is known for these visually eloquent quilts that really speak to African and African American past, a kind of diasporic story.

Liz: Her work is based on photographs of Black people.

She's going back into history, looking at archives, looking at thousands of photographs to find just the right ones to show us something that we've never seen before.

Bisa: I'm drawn to black-and-white photos.

I'm wondering who are these people, and what was the circumstances of their life?

♪ I'm sketching on top of a blowup of the photograph.

I'm looking at what's the lightest light, the darkest dark.

The black and white allows me to imagine how can I use color and fabric to tell this story about this person?

If I'm using a lot of blues and greens, I'm using that cool color palette to say that this person had a more calm demeanor.

But if I'm creating a portrait of somebody who I really want to express is very powerful, you might see me use a lot of colors that look like fire.

♪ I really like African fabric.

This is Nigerian wax-resist.

Originally, these patterns were done as a part of a secret society and a secret language that was only understood by a few.

So, this is known as "speed bird" in the Congo.

It meant that, for them, money is easy come, easy go.

Once you have it in your hand, it speeds right out.

I use this fabric in so many of my pieces in different colors.

It was originally called cours de cheval.

But in Ghana, the women called it "I run faster than my enemies."

A lot of my portraits, I'm trying to embellish them with messages taken from the patterns to reinforce the story.

[Turntable scratching over music playing] ♪ Johnny: Bisa and I met in college at Howard University, and I was a DJ then.

I'm a DJ now.

She was an artist, a visual artist.

So, I'm an audio artist.

So, that's what made us connect.

I am playing for all of Bisa's exhibits, for her openings.

Bisa: I share a studio space with my husband, John.

He's playing music while I'm working.

[Sewing machine whirring and music playing] ♪ It really helps to have another creative person's perspective to think outside of my own box.

♪ After I graduated from Howard, I thought, "Well, I want to be an artist.

So, I should paint."

But it didn't mean that painting really spoke to me.

♪ I wanted to make a portrait of my grandmother.

We all knew that she wouldn't be with us that much longer.

I used my grandmother's fabric remnants, and that made the portrait that much richer because it was made from her life.

That was the first portrait that I created.

I decided to go to grad school, and my master's degree was in teaching art.

And so, I was an art teacher.

But after about 12 years of that, I went to being an artist full-time.

Johnny: She elevated from just a person who could sell some pieces to then saying, "Now I can really take this to another level."

Bisa can create a face that you would actually think is someone looking at you, but it's all fabric.

It's pinpoint precision.

That's where Bisa is with it.

♪ Bisa: We are in a time where people are very separated.

So, I'm looking for images of people who are intimate and tender.

The piece that I'm working on right now is of a young couple taken in the 1970s.

I'm drawn to their gaze.

They look so proud to be a couple.

And I remember that feeling in high school, like, you're boyfriend and girlfriend.

So, the fabrics for the clothing I want to reflect, yes, these are children of African descent, but they're very much American children, and they're very much in the 1970s.

So, I'm using the African cloth, and then I'm also layering that with colored vinyl on top of it.

♪ All of these glittery fabrics emulate the light that I feel is shining from these people.

♪ I'm looking forward to my show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

It is going to open in the fall of 2027.

♪ Dalila: The Smithsonian American Art Museum is incredibly fortunate to have Bisa Butler's largest, really the largest quilt that she's made.

Bisa: I spent so much time with these guys.

Dalila: The quilt is called "Don't Tread On Me, God Damn, Let's Go, Harlem Hellfighters."

Bisa: In World War One, France needed boots on the ground, and the United States said, "We can loan you these Black soldiers."

The Harlem Hellfighters were a segregated unit.

They suffered the largest number of casualties out of any other unit in the U.S.

Army at that time.

[Machine gun firing] They fought fiercely for their country, and they're fighting for their own dignity, and they're fighting to stay alive.

And the photo that I'm drawn to is the soldiers on the boat before they land at New York Harbor.

They're getting ready to be greeted by a ticker-tape parade.

They marched right down Fifth Avenue.

You could feel the thundering of their boots as they came.

And for the first time, Black soldiers were being cheered on by an interracial audience.

♪ Liz: It's a monumental quilt.

♪ You get in close and see the intricate stitching to create this illusion of three-dimension and layers to make this piece come alive.

Bisa: This fabric, the blue and the pink, is Nigerian wax-resist.

You see the circular symbols within the cloth.

That represents the idea when you drop a pebble in water and the rings, how your small input affects the whole world.

-Wow.

-Wow.

♪ Dalila: Her work is really a lesson in empathy and a way of helping us understand and commune with a past that has often been forgotten, overshadowed, or deliberately buried.

♪ Bisa: I do want my work to make people feel good when they see it.

But when Black people look at the artwork, they should see something that speaks to them about where they came from... ♪ To feel the emotional resonance of the artwork.

♪ ♪ [Door closes] [Metal clinks] ♪ Ubaldo: I am a silversmith, and goldsmith, a metalworker, an alchemist, art historian, all these things put together because I like life, and I like to explore things.

So, maybe I can say I'm an explorer.

♪ Silver has been an extremely important metal since antiquity.

♪ And I consider silver the most beautiful metal, much more beautiful than gold.

I find gold a little vulgar.

♪ But silver is beautiful because it reflects light.

As you walk around an object, you see that all the reflections change.

So, in my work, I try to control those reflections to make silver dance with light.

♪ The soup tureen with the fish and everything was created with the reflections in mind, but all the movements are the movement of a boat just an undulating calm sea.

That is the one the fisherman prefers.

[Horns honking] ♪ My family in Rome, we're four generations silversmiths and goldsmiths.

My great-grandfather, his name was Ubaldo, like me.

He opened his shop, and then my grandfather had his shop, and then my father had his own workshop by the time he was 24.

The family concept was that the moment you reach a certain age, you will go on your own and opening your own workshop.

Yeah, that's fine.

That's it.

Thanks.

This is good.

This is it.

[Hammering] But to be a silversmith, the training is not, you know, just to work the metal.

The training is to study art, art history, and design.

So, I was sent to the Academy of Fine Arts and Sculpture in Rome.

♪ I was a great admirer of Pope John the 23rd, and I create for him in my father's workshop a gold ink stand and a pen.

It was given to him as a gift.

I was 17.

♪ There was this American girl that I met at the academy, and that was the reason why I came to America September 27, 1967.

A few months later, we got married.

I worked in New York for nine months.

Then I opened my own place, and I got a commission from Tiffany and then Steuben Glass, Cartier.

I was very fortunate.

♪ [Tapping sounds] Most silversmiths use the repousse method.

That means being chased from both sides.

This is actually an impression from a 17th-century German basin.

Once I make the drawings, these drawings will be put on a piece of metal that is embedded in pitch.

And we trace the drawings down into the metal.

Then we start sinking the masses.

[Tapping sounds] Once you have totally sunk the figure from the back, then we'll remove from the pitch, and we turn it around, and that's what we have, the relief.

From this on, now you have to finish the front.

You are putting all the details on and the sharpness of the figure.

[Tapping sounds] For the goldsmith, silversmith, metalworker, the hammers are the most important tool.

♪ And to use my favorite line from a Michelangelo poem, no hammer can be made without a hammer.

So, with a forge, we can make our own.

Each one of them has their own use, and you can see they're all different.

♪ This is a planishing hammer.

You do not strike it.

You just caress it... so that you are smoothing down the silver.

This is my favorite.

♪ I've used this probably 10 times more than any other.

♪ Mwah.

[Chuckles] ♪ My family constantly restores objects bought for museums and private collections.

Sometimes they were religious objects, like Judaica.

I restored several Torah crowns.

They were in terrible condition, you can imagine.

They were buried during the war.

We restored the original beauty, but I will not touch them till I research the history of the object.

You want to transpose yourself into the person that created it.

It's almost like the artist that made it is telling you, "That's what I meant.

Make sure you respect me."

♪ When I was a teenager, maybe 18, I went to see an exhibition on the American Revolution.

One of the things that caught my eye as a silversmith was the Liberty Bowl.

It was made by Paul Revere.

Nina: A lot of Paul Revere's silver is fairly regular, and some is quite spectacular.

After the Revolutionary War, he's doing fluted teapots, which are really the hallmark of his ability.

They're really quite remarkable.

His father, Apollos Rivoire, was French.

He came to Boston at the age of 13, learned a trade, he opened a shop, brought his son Paul into the shop to apprentice.

Paul does eventually take on his father's shop.

Paul Revere carves out his niche as being a silversmith that can make whatever you need.

Paul Revere is not only doing this himself.

He has a team of apprentices and journeymen who are working in his shop.

So, he's already starting to think pretty early about how he can expand his business.

♪ Nina: The Paul Revere House, which was built around 1680, is the oldest surviving building in original Boston.

David: By the time the Revere family moves in in 1770, it's a little bit of a fixer-upper, but his silversmith shop is going to be located a few blocks away.

So, the location is perfect.

[Drums playing] Nina: The buildup to the Revolution is not military action.

It's community activists.

David: The Liberty Bowl is actually commissioned by the Sons of Liberty, this rebellious group that's stirring up troubles here in the colony.

Their ideas are that we are being taxed without representation, the idea that we will separate from the United Kingdom.

On this bowl, Paul has engraved the names of those Sons of Liberty members, and this is a kind of revolutionary act that he is doing, to be affiliated with this act of rebellion.

Ubaldo: Next to it in the exhibition was Paul Revere's engraving of the Boston Massacre with the names of the patriots that died.

It moved me tremendously that a silversmith made these objects.

Nina: So, he's the person who is chosen for the midnight ride.

"One if by land, and two if by sea."

It turns out the British troops are going by water.

And so Revere is rowed by two friends across to Charlestown.

He borrows a horse and rides off.

He gets to Lexington.

He has alerted people along the way.

"The British troops are coming."

And so he becomes our favorite patriot and silversmith, Paul Revere.

♪ Ubaldo: After I moved to America, I restored more than 12 objects of Paul Revere.

I remember the first one was a simple teapot.

In a sense, it's like looking at an old friend, like say, "You know, I met you in Rome.

You don't remember me, but here I am."

[Ladder rumbling] Helena: When I'm weaving, I forget everything else.

It's a great pleasure because the wool is wonderful to touch.

And I'm totally absorbed.

This goes in here.

It's what I've always wanted to do.

I've never ever thought I would do anything else.

♪ Mae: Helena Hernmarck is an absolutely masterful tapestry artist.

She combines skill with incredible design talent, weaving tapestries on a truly monumental scale for architectural settings throughout the country.

She has woven many of these pieces at her own studio on her large 11-foot looms.

Many of them are also woven at her kind of partner, sister studio in Sweden.

♪ Helena: I grew up in the old town in Stockholm, which is a very charming island.

My father was head of decorative arts at the national museum.

When I was 17, he took me to visit Alice Lund, who had a weaving workshop, and my father said, "Do you want to be a textile designer?"

And that decided my fate.

After four years in art school, I married a Danish fellow, and it was with him I moved to Canada.

♪ We were there just in time for Expo.

And some people at the National Film Board commissioned me to make a tapestry for the lobby of the Labyrinth, their building at the Expo.

And the design I made was a snake that was like a labyrinth and lit from behind like a stained-glass window.

I felt if you want to make an impact in the lobby, you do something big.

That was really the market that I would seek, would be lobbies.

This is like watching grass grow.

It's always slow.

Now it's more like embroidery than weaving.

When I got the commission from the Weyerhaeuser Company, I was told, "Fly to Seattle, stay in the tall hotel, "go up on the roof, and wait for the helicopter to pick you up."

So, there I am, 29 years old, like James Bond on top of the roof.

♪ They flew me to walk around in the rainforest, and in those days, I hadn't done much photography.

So, I decided to work from a picture they had.

And then I went back to Montreal and wove the rainforest tapestry, and that was my breakthrough.

♪ Mae: Helena has evolved this historic tapestry medium to reflect photographic vision.

And so, weaving with this incredible sensitivity to color and focus is something that she has innovated.

♪ In '72, I had by then married an Englishman.

We then moved to London.

But the next big commission I got was from Bethlehem Steel, three tapestries.

I was just given the photograph.

So, I said, "Well, that's great.

I can do it like that."

♪ You have firelight coming in one direction, and the daylight is coming in another direction.

I like that mix of light.

♪ In '75, I moved to New York.

America was where I could enlarge on my career.

I couldn't do that in England particularly or Sweden.

I then married the industrial designer Niels Diffrient.

He grew up in Mississippi, and he turned out to be very clever, going to Cranbrook, having a Fulbright, and then focusing on ergonomics and the human body.

And he developed the Humanscale chairs, which was really totally unique.

♪ Niels designed this room for me.

Mae: Walk into the studio, and the first thing you see is the wall of wool.

This is more than 2,000 colors and arranged according to the spectrum.

Helena: I've got all these colors, but they're never exactly what I need.

So, I combine them.

I have a sample of what I'm looking for, and then I lay them out.

So, it's, in fact, five different yarns.

So, then I go up and find each one.

That's one.

Then this is... this one.

That one.

And then we have the green over there.

And then we have a light one like that.

Okay.

So, in effect, I'm making one color out of five colors.

And then I can tie onto here.

Then it will continue.

♪ In 2013, Niels got cancer.

For eight months, I stopped my work to take care of him.

But I felt that I could allow myself one hour a day to do something that I would enjoy, and that's what these are.

I made probably 200 of them before he passed away.

♪ What you see here is an overview of my tapestries.

As I look around, almost every state has a piece.

This is Atlanta.

That's the biggest one we made, is 400 square feet.

And these are Oklahoma, the history of Oklahoma.

Then the history of money and the future of banking.

So, banks are involved.

And this was for Pitney Bowes originally, these tall abstract works.

And they now belong to the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

And this is in Texas.

It hadn't occurred to me until then that you could weave in focus and out of focus.

That was the first time I did that.

[Traffic sounds in distance] Mae: The Hudson Yards commission was an incredibly ambitious project.

Helena: They wanted two tapestries for the elevator lobby, and the client said, "I want it to go up the wall and along the ceiling."

Of course, we had never done anything like that.

But you always say yes.

Never say no.

Mae: For the better part of four years, there were two weavers in Sweden weaving both the wall tapestries and then the ceiling tapestries.

And then simultaneously here at Helena's studio, we wove various ceiling hanging solutions.

Helena: We needed to keep the ceiling tapestry exactly flat.

So, at every inch, there had to be a carbon fiber tube.

Mae: This backing would allow it to be suspended flat across the ceiling.

♪ ♪ Helena: I'm trying to get what I want.

But it's a particularly tricky piece of weaving right now.

♪ Colette: Pop-up books are this flat object... and then, all of a sudden, you open it, and this scene emerges that just seems like magic.

♪ And that's what intrigued me.

[Gong rings] I was born about an hour from downtown Philadelphia.

Come on, Nor.

♪ My parents emigrated from mainland China.

They both came in the 1950s.

And it was a pretty happy childhood.

Back then, parents just wanted you to assimilate.

They didn't want you to learn their native language.

When I became a teenager, I wanted to hide that I was Chinese.

I used to peroxide my hair, and I wouldn't eat Chinese food.

My father was an engineer.

I think he always wanted me to become an engineer.

But that's the one thing I didn't want to be because he wanted me to be that.

And after college, my mom found a tour for me to China.

The tour visited Yunnan Province.

Kunming is the capital, and it's where my mom was born.

Yunnan has almost half of the 55 ethnic minority groups of China.

When we visited the university for ethnic and minority groups, the dean asked me if I wanted to teach English there.

I was offered that job because my great-grandfather, Lung Yun, was governor of Yunnan Province and general of the army, and he had this nickname, "The King of Yunnan."

For them, it was, like, an honor to have a descendant of Lung Yun at the school.

So, I taught English, and I also started traveling.

♪ I learned during my first trip to China that my mother was from an ethnic minority group called the Nuosu Yi.

So, I wanted to explore the cultures of the different minority groups.

♪ I stayed for three years, taking pictures of things I'm seeing and experiencing.

♪ And then I went back to the States to get my MFA in photography.

But being a photographer is really competitive.

and so I thought, "How can I make my photographs more interesting?"

I just went and did some, like, research in the bookstore.

Like, "What can I do now?"

I used to go there to... to think.

And in the children's section, I saw for the first time pop-up books.

♪ I took them apart and analyzed them.

There were parallel lines and angles, a lot of mathematical relationships.

Also, a whole story could be told without words.

♪ So, I learned how to make my own pop-up books.

And then I incorporated pop-up mechanisms with my photographs.

Three years later, I went back to Yunnan Province to create a series of pop-up books called "We Are Tiger Dragon People."

♪ The most difficult part is actually not the mechanics.

It's the story.

♪ I wanted to have a reason why it's three-dimensional.

Festivals or celebrations are good because people want to be photographed.

♪ The mechanics of a pop-up are a series of simple basic structures combined together to create something more complex, and then adding photographs makes the viewer look at it with surprise.

♪ This series has three eggs with images from my trip to see the Miao people.

The Miao are very well known for their festivals and for their paper-cutting.

I went to this cave where a family has been making paper for 19 generations inside.

♪ The Miao believe that their originator was called Butterfly Mother, and Butterfly Mother gave birth to 12 eggs, and these eggs are the origin of all living things, including the Miao people.

♪ This sculpture is called "Noodle Mountain."

I wanted to understand the history of Chinese laborers coming to the US during the 19th century.

♪ The Chinese helped build the Transcontinental Railroad, and Chinese laborers were working in the salmon-canning industry.

But the locals wanted them out because they claimed that they were replacing American workers.

[Gong rings] So, the Chinese were targeted with massacres, hangings.

The red sauce represents blood, and fire represents the many Chinatowns that were burnt down.

In 1875, the Page Act was the first legislative act that targeted immigrants, and it mainly banned Asian women from the country.

And then in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act excluded all Chinese men from coming to the US.

But there was a loophole that allowed merchant visas for businesses, and one of those was restaurants, leading to an exponential growth of Chinese restaurants.

♪ The crank reminds me of when I was little and my father would use a manual pasta maker.

♪ He always wanted me to become an engineer, but he was just happy that I had found something that I liked.

And then the irony is that I am an engineer now, a paper engineer.

♪ Roberto: I come from Kensington in Philadelphia.

Another name for Kensington is "The Badlands."

It's where a lot of impoverished people live.

That's how people look at it from the exterior, but from the inside, I see that it's a community of resourceful people.

And there's a lot of creativity that happens in this place.

♪ I am a potter, poet.

I'm an artist.

The work I do is primarily representing the community that I come from.

I am trying to find my identity through that work.

♪ ♪ My parents are both from Puerto Rico.

They did emigrate here.

They come from less means than I did.

In school, we didn't have art classes.

That wasn't really a thing.

I would say my first introduction to art was graffiti.

I had some big cousins, and I just wanted to be just like them.

We all did graffiti together.

When I would tag a wall with my name, it made me feel like my life mattered.

And so I started to draw and paint.

♪ Years later, I took a community college art class, and the teacher just happened to be a potter.

[Slapping sounds] That was why I initially pursued ceramics.

It was the first time really where people were starting to tell me that I was good at something.

I told myself that I was gonna have a career in the arts, and I was gonna do it at all costs.

[Machine whirring] ♪ My practice became defined when I started to acknowledge where it is that I'm from.

It was telling the stories of Kensington, but also paying homage to all the people that paved the way for me to be here.

In this piece, I wanted to make something based off of Nina Simone, and I wanted it to be the era of the seventies.

♪ I do design directly on the work, but a lot of it is just back and forth between me and the pot.

♪ Jennifer: Roberto Lugo is really important to this neighborhood and to really the whole ceramic community nationally and internationally.

♪ We have his beautiful mural that's on the side of our building.

And he wants to make sure that young people from his community have a chance to do ceramics, which is really empowering and gives kids agency in a world where they often feel powerless.

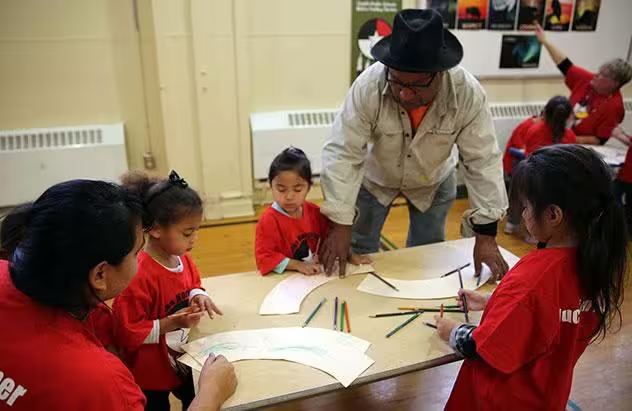

[Rattling sounds] [Water pouring] Roberto loves to go out into parks and throw on the wheel.

It's a surprise for people seeing someone doing this thing that they really have never seen before.

So, make your fingers like this.

Yep.

And you're gonna put it right in the pot.

-Isn't that cool?

-Yeah.

You want to try to make some pottery?

Since I winded up being somebody who has a career in art, it becomes more important for me to share that.

Perfect.

You're doing so good, Mia!

Look at that!

So, what would you eat out of this?

-Cereal!

-Cereal, yep.

Good job!

♪ Just recently, I got to teach people who live in Kensington about pottery patterns and how they're made.

And they got to make their own patterns.

♪ We used those patterns to paint three public sculptures.

So, the public sculptures are not only in this neighborhood, where people don't think public sculptures belong, but that they're created by people from this community as well.

♪ I'm inspired by ancient Greek pottery, and those potters were working in the same exact way that I'm working today, except they did it several thousand years ago.

Just to be a part of that lineage for me is really exciting.

Carolyn: In this exhibition, we have incorporated ancient objects together with Roberto's work to show how ceramic vessels tell stories, both in antiquity and today, how that medium really enables these stories to be told and shared among a community.

Roberto: If we look at ancient Greece, the pieces are telling the stories of gods and incredible parties and heroes.

But you don't really see the poor people or the enslaved people, and for me, it's so important to tell their stories.

Carolyn: We have his work called "Same Boy, Different Breakfast," where, on one side of that vessel, you see a teenager sitting in his room at his desk.

Roberto: In the back of the piece, it has the very same boy, but in a prison cell.

It tells my experience of growing up with young men who were innocent but they wind up somehow in prison.

In this particular piece, I was thinking a bit about, when somebody passes away, and they create these street shrines, sometimes people will pour out some beer for the departed.

Carolyn: It reminds me of a type of scene that you see on Greek funerary art, where the living and the dead are shown holding hands like this, and that's really what you see here with these individuals reaching out to each other in the face of death.

It's just very powerful.

♪ Roberto: One of my works is at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

It's actually a life casting of my body broken up into all the different parts of my DNA.

And it was part of an exhibition directly named in the presidential order to remove the idea of race from art institutions.

I feel like people fear it because they feel like their lives or stories don't matter, but all of our stories matter, and we should celebrate them all.

♪ So, when you cut the arts, baby, you cut the heart strings off the body that freedom rings.

If you cut the arts to fund war, what are we fighting for?

They tell us to paint houses but not to paint a canvas.

You'd rather see us in encampments than exceeding on a campus.

Without art, how you gonna dance when you ace that math test?

Who's gonna sing your praises when you get that high mark?

Without art, we're quick to draw guns, apt to sing war cries, dance around the issues.

You want to stop violence?

Pick up some violins.

You see, because those who draw good are the last to draw blood, and those who throw pots, we're the last to throw shots.

So, when you cut the arts, baby, you cut the heart strings off the body that freedom rings.

♪ Announcer: Stream more "Craft in America" on the PBS app.

♪ "Craft in America" is available on Amazon Prime Video.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S17 Ep1 | 1m | Watch a preview of EAST highlighting diverse expressions behind modern craft in the eastern region (1m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by: